New Benchmark Set In Endurance Swimming

UK strongman Ross Edgley, who you may remember from such feats as rope climbing the height of Everest, and recently swimming 100km in the Caribbean while tied to a tree, has now completed his mission to swim around the entirety of mainland Great Britain – all 3200km of it; crashing coastline, unruly weather, the works. We thought we’d share this great article from ABC’s Steve Wilson.

Adventurer Ross Edgley returned on Sunday to the Kent town of Margate, in Britain’s south-east, 157 days after he left.

Stepping on to dry land for the first time in over five months, he became the first man in history to complete a 2,800-kilometre circumnavigation of Great Britain — swimming unassisted the whole way.

The 33-year-old Briton first took to the water on June 1 this year. His days following consisted — weather allowing — of two six-hour swims, often in the dark of night, with periods of rest on board a boat in between.

On many days he covered enough distance in the water to have comfortably completed a swim across the English channel.

He did not take a day off through sickness or injury, with the only stoppages on his journey enforced by extreme winds and waves.

“It feels a bit weird on land,” he said as he reached the end of his final swim, “a bit too solid for my liking! I almost fell over when I started to jog into shore.

“Setting out, I knew [it] would be the hardest thing I’ve ever attempted. I was very naïve at the start, and there were moments where I really did begin to question myself.

“My feelings now are pride, tiredness and relief. It’s been a team effort and it’s thanks to the whole crew, the support I’ve received from the public.

“To see so many smiling faces here today is amazing, and if I can take one thing away, it’s that I’ve inspired people, no matter how small that inspiration may be.”

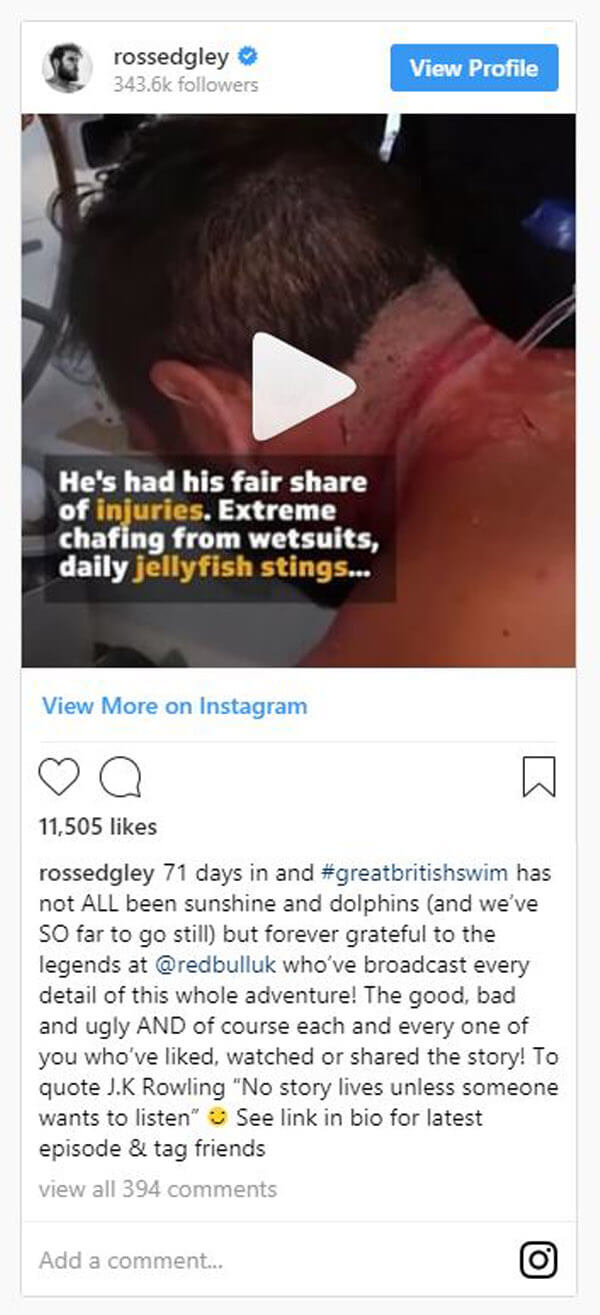

Along the way he battled strong tides and currents, icy water off the coast of Scotland, storms, three-metre waves and numerous jellyfish stings.

Even out at sea he could not escape some man-made problems, either. When navigating the Humber estuary waters, he found himself in the middle of a large amount of what was effectively sewage (“the poop pipe of Great Britain,” as Edgley himself described it, “like swimming in a toilet”).

Rotten feet and a disintegrating tongue

The toil the endeavour has taken on his body is almost unimaginable.

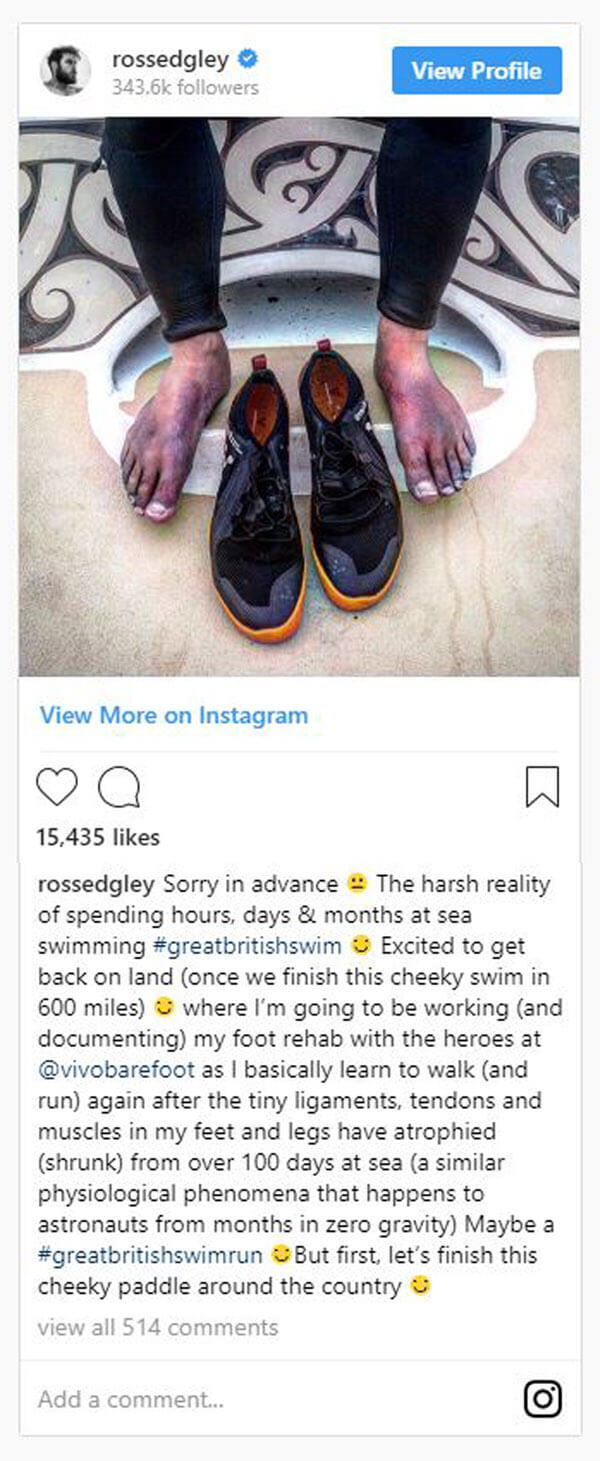

Being in sea water for such prolonged and sustained periods saw his hands and feet at times show signs of what is effectively “trench foot”, the skin rotted by the elements.

Barely a month in, he was already experiencing “salt mouth”.

Constant submersion in the sea water left him struggling to eat, swallow or talk due to the dryness of his mouth and throat.

He woke up from one sleep to find chunks of his tongue had fallen off and decorated his pillow.

The back of his neck — despite the use of three kilograms of Vaseline and five rolls of gaffer tape to prevent it rubbing the top of his wetsuit — bears the scars of extreme chaffing (or “rhino neck” as he dubbed it), a sensation he likened to rubbing sandpaper on the back of his neck for several hours twice a day.

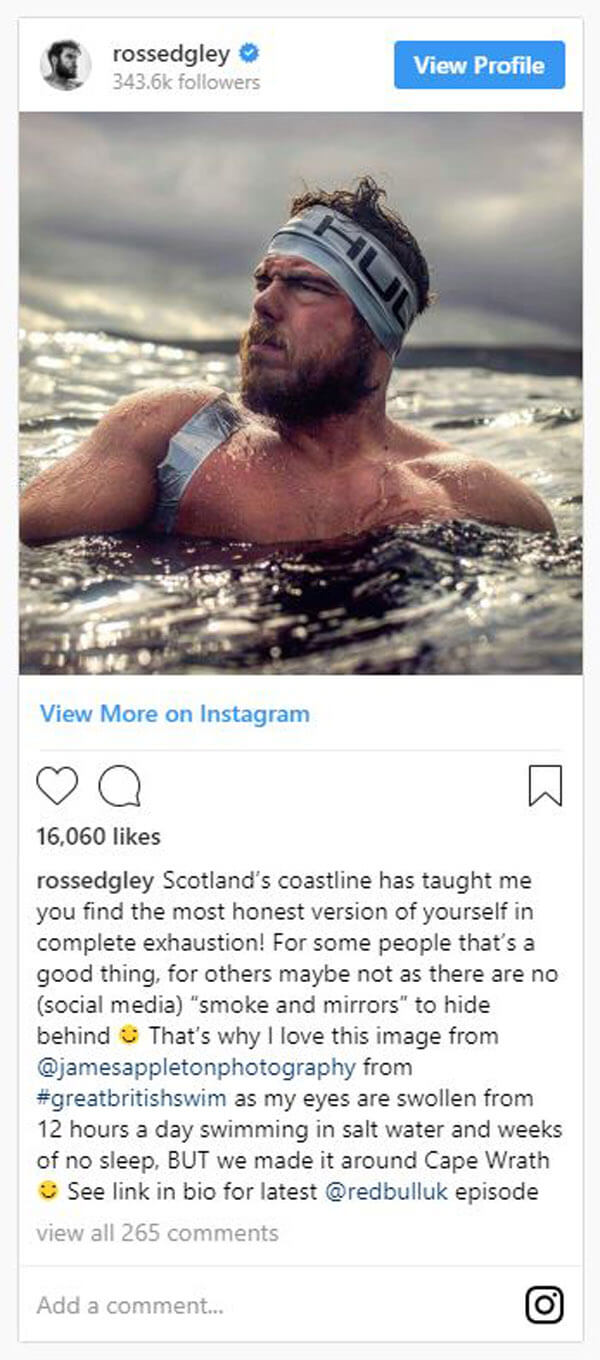

The severe cold of the water — averaging between 15 and 20 degrees Celsius — often left him shaking uncontrollably when returning to the boat. Space blankets and hot food were his best protection to fight off the onset of hypothermia.

For the last few weeks, as the finish line came in to view, the business of finding his land legs occupied his time between the water and his bed.

After spending so much of his time, for such an extended period, in a horizontal position he had almost literally lost the ability to walk.

A physiotherapist attending to him confirmed he has lost muscle mass and bone density.

He has since been conducting exercises designed to put strength back in to his feet and calves, images of which show him moving with the gracelessness of a toddler taking their first steps.

A solo mission with many helping hands

The rules of the self-devised, and previously unattempted, contest meant that in order to complete the task successfully Edgley could not touch the shore once.

He was aided throughout by a team of support staff, including medics, though principally relied on the expertise of sailor Matthew Knight, who piloted his catamaran, Hectate.

He worked with the local Royal National Lifeboat Institution (RNLI) to chart the currents and wave patterns in the seas. The six-hour periods of swimming and rest were designed to mirror the changing tides of the water he was navigating.

Genuine deep sleep often eluded him. And the constant disruptive sleep only added to the stress on his body and mind.

He used no buoyancy aids “in the true spirit of endurance swimming”, just gloves and thick wetsuits and head covers.

He carried with him a wardrobe of wetsuits of gradually decreasing sizes to account for the weight loss the physical effort produced.

Edgley grew a healthy beard not just to avoid the inconvenience of shaving, but also to act as a degree of protection against jellyfish; with his head leading the way it was most exposed to them.

Minke whales, a pod of dolphins, sea otters and curious seals were more welcome swimming partners at other times.

He survived on a high-calorie and high-carbohydrate diet of whey protein, nut butters and coconut oil.

He burned through 15,000 calories a day — more than half a million across the whole swim — and so was also able to tuck in to pizzas, burgers and ice cream.

“You have to train your digestive system to eat anything,” he said. “There is method to the madness of having cold pizza with a super greens shake in the morning. There is no blueprint for this.”

His most trusty source of food, however, was the humble banana. More than 500 were consumed from the time he began the adventure.

Records broken, new ones invented

The initial estimate of how long the trip

would take was set at an ambitious 100 days.

The trip ended up taking half as long again. Though along the way Edgley ticked off a number of notable records.

On August 14 he recorded the longest-staged sea swim, adjudicated by the World Open Water Swimming Association. That was 74 days in to his adventure. Less than half-way.

As much as it was a physical challenge it was also a mental battle. One that few others could even contemplate.

“It’s about finding normality in the abnormal. This isn’t a traditional sporting event,” he said.

“With a marathon, you can grit your teeth knowing you can get through it and you’ll be in your bed with a bubble bath at the end of it. I can’t do that.

“I’m constantly in the cold water or in my bed, which is rocking side to side in the waves, but as long as you make peace with that fact, the Great British Swim becomes possible.”

A history of adventure

His philosophy on the adventure all along was he needed to be “naive enough to start and stubborn enough to finish”. His arrival back on the Kent shoreline this weekend more than attests to the latter; the smile on his face throughout pointing to the former.

It should come as little surprise to anyone who has followed his past adventures.

Edgley is made of special stuff, this undertaking was just the latest, perhaps greatest, of a long list of incredible, if slightly off-the-wall achievements.

In April of 2016 he completed a rope climb that was the equivalent height of Mount Everest in 19 hours. In the same year he broke the tape on a marathon in which he gave himself the impediment of having to drag a car the course distance.

A window in to his unique personality, however, was perhaps best offered last year in an event he ultimately, and unusually, failed to complete entirely. A 40-kilometre swim between Martinique and St Lucia was always a challenge. Even more so when he attempted it with an actual tree trunk tied to him.

Currents took him off course and he had to abandon the effort. Though he estimates he swam the distance anyway, just not in the direction he had hoped.

All of Edgley’s adventures have at their heart a message of inspiration and fitness. Not a fitness designed to grace the cover of fashion magazines but, as he says himself, “fitness for a purpose”.

“I want to inspire people to get out there and challenge themselves,” he said, “maybe try your first open-water swim, sign up for a triathlon, or your first park run — find something that you didn’t think you were capable of … and prove yourself wrong.”